photo: Jaroslaw Praszkiewicz

The life of Prisoners

Extract from "The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors"

The Zigeunerlager was a specific place. Families could stay there together, prisoners could have their own clothes, money and belongings. Those who could afford it, could buy food. Prisoners were not permanently employed in the camp’s working units but from time to time could be sent to perform some maintenance or construction work.

From the perspective of the prisoners, the family character of the camp could be seen as a factor contributing to the sense of debasement. Crowding in confined space caused the violation of all cultural rules regulating the relations between Roma of different gender, age and group affiliation. The traumatic memory of the situations in which cultural taboos could not be observed was increased by the trauma of those subjected to sterilization in the concentration camps and by the terrible experience of sexual violence against women. Given the strict norms regarding sexuality in traditional Roma cultures, such experiences must have left an imprint on the victims and their nearest ones that was hard to bear.

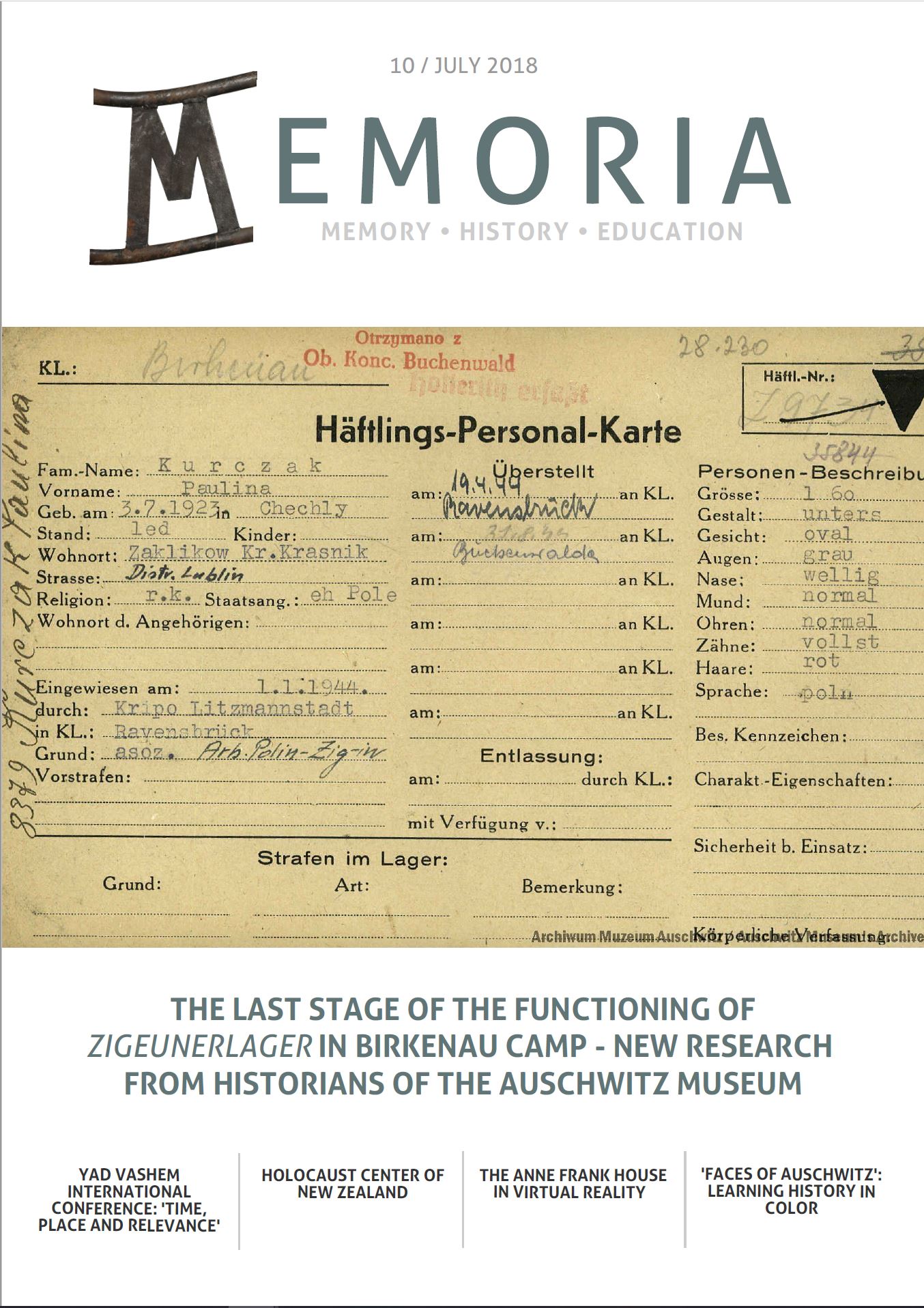

Clothing and prisoners’ markings

In the beginning , the prisoners in the Zigeunerlager wore their own clothes and their hair was not shaved.

The Gypsies brought in at the beginning of 1943, who populated sector BIIe in Birkenau, went around in their civilian clothing. They had a piece of cloth sewn on the left side on the front of their outer garments in the shape of a black triangle with the base facing downward. To the right of the triangle, slightly lower, was the letter Z (short for “Zigeuner”), and next to that the number of the given Gypsy prisoner...As for the Gypsies from sector BIIe, we in the Bekleidungskammer [camp warehouse for prisoner clothing] were ordered before their arrival to prepare 30,000 rag scraps with the insignia they wore, as I have described them.

Account by Jerzy Adam Brandhuber, a Polish prisoner of KL Auschwitz where he was assigned to work in clothing storage. APMA-B. Accounts, vol. 95, 218.

Work

There was no compulsory work in the Gypsy camp. Gypsies labored outside the camp building roads and doing various kinds of work connected with camp maintenance. Those capable of working went by wagon to get sand, stones and turf needed to build roads inside the Gypsy camp. The Gypsy women went out every day for herbs used in the camp soup.

Account by Tadeusz Joachimowski, a Polish prisoner of KL Auschwitz, performing the function of a scribe in the Zigeunerlager. APMA-B. Statements, vol. 13, 56-80.

Some of the Roma prisoners were forced to do hard work deepening drainage canals in the Zigeunerlager, as the following account confirms:

We had to get up very early. For breakfast they gave us dishwater-you couldn’t even call it coffee. If you had a little bread from the previous evening you were in luck, because they didn’t give us anything else. Then they counted us; we all had to stand in front of the boxes. Those assigned to a labor detail had to step forward. Outside, on the camp street, they counted us again. Woe betide us when someone was missing, because then we all had to stand there, and time after time the sick ones hid themselves and weren’t there, because they had lost so much of their strength that they were half dead. I was assigned to the Kommando building the sewers in Birkenau, and I was then fifteen or sixteen...We didn’t have shoes or socks, and there were storms and it was raining. Everything was wet and we had to dig up the clay without stopping. The sewer was supposed to be two-and-a- half meters deep, and over us stood a Kapo with a big club, urging us: “Faster! Faster!” At noon there was a break. Everybody had his own tin bowl with him, and whoever didn’t line up straight when they were passing out food got it over the head immediately with that bowl. After a break of half an hour we had to go back to work until four or five o’clock, depending on the time of year. Then they counted us and we went back to the barracks. Every evening, the names of the dead were read out...The camp street in Birkenau was full of corpses lying around in piles...At night, when everything was freezing, they loaded the frozen corpses on trucks and took them away.

Account by Franz Rosenbach, a prisoner in the Zigeunerlager. Source: Inaczej wyobrażałem sobie Auschwitz, [in:] Wystarczyło urodzić się Cyganem, „Pro Memoria”, no. 10.

The Canteen

In the Zigeunerlager there was a canteen, in which prisoners who had money could buy food, mineral water, cigarettes, etc.

Only Gypsies and the sanitary service could make purchases in the canteen. In a kettle with a capacity of three hundred liters and located in the canteen barracks, we cooked the soups known to the prisoners as Kantinsuppe every day: milk soup, vegetable soup, and red beetroot soup...We cooked the soup from ready-made mixes supplied in packets, and even the beetroots were supplied to us in cans. We cooked a full kettle every day and sold it all. The Gypsies paid cash at first, and scrip was introduced at a later period. The daily turnover was high, and fluctuated in the range of sixteen to seventeen thousand marks. When the scrip was introduced, the turnover decreased.

Account by Marian Perski a Polish prisoner employed in the canteen in the Zigeunerlager. APMA-B. Statements, vol. 61, 197-200.

Relations between prisoners

There are different testimonies regarding the relations between various groups of prisoners in the Zigeunerfamilienlager. Some witnesses emphasized the great solidarity and mutual help among prisoners. Referring to such testimonies, Kazimierz Smoleń (himself a former prisoner of KL Auschwitz) writes:

In spite of the fact that deported Roma were coming from different countries, one could not notice any conflicts between them. They all created great solidarity, offering each other help. There were no fights or quarrels and families disciplined their little children. Family ties were very strong. In the barracks they tried—despite the inhuman hygienic conditions—to keep order and cleanness.

Kazimierz Smoleń, Cyganie w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau [in:] J. Parcer (ed.) Los Cyganów w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau. Oświęcim 1994.

The inhuman conditions in the camp, together with the ever-present violence, dehumanization and struggle for survival were, however, the occasion for a different type of testimony, accounts of conflicts between prisoners from different countries, and abuse of their position by prisoner functionaries.

Categories of prisoners

In the Zigeunerlager there were various groups of Roma and Sinti, sometimes differing very much from each other. There were Roma who observed the traditional Romani value system and the rituals that protected it and there were Roma who did not live according to that system. There were well-off prisoners who had enough money to afford better nutrition, therefore increasing their chance of survival. There were also soldiers dismissed from the Wehrmacht, who did not fully understand why they were sent to KL Auschwitz. There were educated people and professionals. And there also were the poor, who could not count on anything.

In more or less the fourth block from the kitchen lived the rich Gypsies...; there was always an abundance of cigarettes, food, and drink there... The Gypsies from Bohemia...had a block of their own at the beginning, but were later divided up. They came from Moravia, and the richest among them were the boilermakers. They were the camp elite...Some of them...worked in administration. Many of the girls had diplomas from the Commercial Academy, spoke German, and knew how to type.

Account by Jana Češpiva, a Czech prisoner of KL Auschwitz, performing the function of a physician in the Zigeunerlager. APMA-B. Statements, vol. 74, 32-35.

German Sinti/Roma—soldiers of the Wehrmacht in the Zigeunerlager

Gypsy camp—Gypsies from all over Europe currently arriving. They have come from Poland, Bohemia...and Germany. There are more than 12,000 of them; they have a separate camp. Whole families are transported— the elderly, women, children, infants, and pregnant women...They are transporting not only wandering Gypsies, but also assimilated and settled Gypsies, the Gypsy intelligentsia from Germany, artists and German soldiers. Recently after the arrival of a certain transport of Gypsies from Germany, when one of the SS men treated one of the Gypsies in an overly vulgar way, the latter went up to him and insulted him: “You coward, you’re here fighting against women and children, instead of at the front. I was wounded at Stalingrad, I have medals, I outrank you, and you dare to offend me!” The SS man walked away shamefacedly. The Germanized Gypsy was inducted into the German army at the beginning of the war, like many other Gypsies, and was simply on leave with his family, and together with his whole family he was taken away to the Gypsy camp without regard for his uniform and his military service. There are scores of German soldiers here. The majority of them have German medals from this war.

From a report by the camp’s resistance movement, passed to the Polish Government-in-Exile. APMA-B. Resistance Movement Materials, vol. 24, 78.

We learned that among the Gypsies there were soldiers of the Wehrmacht who had been sent on leave, even from the front line, just to have them arrested immediately after their arrival in their homes and put in the camp where they met their family members who had been deported earlier. Among them there were many who had been decorated for bravery and valor in the First and in the Second World Wars...They were proud of these medals and believed that because of them they would be treated in a better way. According to what they were saying, they had been arrested by mistake and would be released in few days. They behaved accordingly toward other Gypsies and, first of all, to the prisoners of other nationalities who constituted the majority of prisoner functionaries. They did not want to do any work commissioned by prisoner functionaries. Only with the passage of time, when they started to understand how hopeless was their situation, they changed their attitude.

An excerpt from the recollections of Tadeusz Joachimowski, a Polish prisoner of KL Auschwitz, performing the function of a scribe in the Zigeunerlager. APMA-B. Recollections, vol. 2003, 50-65.

Educated German Sinti with double identity (Sinti and German)

One of the women working in the office was...very intelligent and smart twenty-year-old Gypsy Hilli Weiss. I was curious about what conclusions she drew from her almost two-month long stay in the camp?...She was still very optimistic and looked to the future with confidence. She told me that she came from Berlin where she was born, attended the school and worked until the time of arrest. She felt German and was convinced that they had been arrested by mistake—in the camp there were also her parents and sister. Her father was even a valued locksmith expert, thus very much needed in the war economy.

An excerpt from the recollections of Tadeusz Joachimowski, a Polish prisoner of KL Auschwitz, performing the function of a scribe in the Zigeunerlager. APMA-B. Recollections, vol. 2003, 50-65.

My father could not comprehend it at all. After all, he’d been in the First World War and was proud to have been a German soldier. This was his Fatherland, the land he’d bled for. My eldest brother Anton, who was also a soldier, was already in Auschwitz in 1943. Before this he’d been in the war, fought in Poland and France, and was even wounded...In 1943, he, his three children and his very pregnant wife were sent with a prisoner transport to Auschwitz [and] “died” of ill-treatment.

Account by Josef Reinhardt, a prisoner in the Zigeunerfamilienlager. In: Memorial Book. The Gypsies at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Ed. by Jan Parcer. München-London-New York-Paris 1993, vol. 2, 1523.

Sìnte aj Rroma and-o Auschwitz

The last stage of the functioning of the ‘Zigeunerlager’ in the Birkenau Camp

Recent research by historians of the Auschwitz Museum

The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz

A guidebook for visitors

The genesis and course of the Nazi persecution of Roma and Sinti

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Block 11

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Escapes

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

“Zigeunerfamilienlager” (“Gypsy family camp”)

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Arrival in the “Zigeunerfamilienlager”

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

The life of Prisoners

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Children

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”

Dr. Mengele and experiments on prisoners

Extract from “The Destruction of European Roma in KL Auschwitz: A guidebook for visitors”